With the APS Hierarchy and Classification Review now released and a focus across Government around organsiational and team structures (including reviewing past APS guidance, such as Optimal Management Structures) I thought I would share some past research in this space highlighting key shifts in organisational thinking & design (its an evolving space!).

What changes or challenges do you have within your public sector organisation regarding organisational structures? Any reflections, comments or feedback? Feel free to comment below :-)

Rise of the Machines

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the first ‘Industrial Revolution’ saw transformational changes to organisational structures, as a response from shifting from agricultural to the industrial economy (Kajewski et al, 2001). These shifts in the early 1900’s saw the adoption of what is called today ‘classical management’ approaches, including ‘scientific management’ (i.e. Fredrick Taylor, 1856–1915, Henry Gantt, 1861–1919) and ‘administrative management’ (i.e. Henry Fayol, 1841–1925, Max Weber, 1864–1920).

'Classical management' is commonly viewed as seeing organisations as 'machines' (Bolman et al, 1989, Morgan, 1986, Mintzberg, 1979) and are characterised by having a deep hierarchy, specialisation of labour, division between management (e.g. senior executives) and staff (e.g. non-senior executives), command-and-control, bureaucratic, with strategy centralised and fixed (Youngblood 2000, Bartol et al 1999, Morgan 1996)).

Since the 1980's however, another transformation in management approaches is well underway. This transformation has seen the adoption of what is called 'contemporary management' (or modern management) approaches, which has been driven from the seismic shifts in organisational operating environments caused by what the World Economic Forum call the third and fourth-Industrial Revolution (e.g. digital revolution and so on).

Contemporary approaches refocus from seeing organisations as 'machines' towards 'organisms' (or ‘behavioural’) focus (refer to transition image from McKinsey&Company below). Over the past 30 years, organisations around the world have been shifting towards modern management methods, that are commonly characterised by having:

- Deep hierarchy to flatter networks,

- Fixed structures to evolving and flexible,

- Top-down control to autonomous cross-functional teams,

- Centralised decisions to de-centralised with guardrails,

- Strategy fixed to strategic thinking shared and evolving

- Individual responsibilities to collective accountability

In the private sector, adopting modern management practices is seen as vital for survival in the economic environment we live in today (Lin, Chiu, & Chu, 2006).

Flexibility

The global pandemic of COVID-19 was a great example of how Governments can pivot and change based on changing circumstances. For example in New Zealand, the Ministry of Social Development (MSB) was able to rapidly shift services online and deploy and scale resources to meet the challenges of the pandemic. Case study into MSBs approach found that it’s adoption of agile mindsets and approaches, including putting people, collaboration and innovation at the centre helped it to respond effectively to the crisis.

A paper from OECD explored elements that helped Governments enhance agility, and a key element was through Resource Fluidity, which is the ability to move resources (personnel and financial) in response to changing priorities, promote innovation and to increase efficiency and productivity in more effective public policies and services. Key elements of resource fluidity included not only mobility of people and knowledge, but also modular team structures.

New Organisational Design

Changing towards new organisational structures to support the new paradigm in organisational management can be difficult, particularly organisations that have entrenched structures and staff with invested interests in maintaining the corporate ladder status-quo (a ladder which can take decades to climb!).

Three Laws of Agile

There are some guiding principles however which can help in this change. Stephen Denning’s three laws of agile (Age of Agile, 2018) provides a useful framework for change. These laws include:

- Law of the Small Team: Work is done in small autonomous cross-functional teams working in short cycles seeking continuous feedback from the ultimate end user (e.g. citizens, etc.)

- Law of the Customer: In Agile organisations, “customer focus” means something very different. In truly Agile organizations, everyone (from top down) is obsessed with delivering more value to customers. Staff have clear line of sight to the ultimate customer and can see how their work is adding value to that customer—or not.

- Law of the Network: Viewing the organisation as a fluid and transparent network of players that are collaborating towards a common goal of delivering with and for customers.

Flatter Structures

A flat or organic structure is better suited to support agile teams than hierarchical ones (Kubheka, Kholopane and Mbohwa, 2013). Hierarchical models are more bureaucratic and traditionally take a top-down approach to establishing and approving processes, decision-making and ways of working. By contrast, flat structures distribute decision-making to those closest to the work. This can allow flexibility in fast-moving environments and empower a workforce to experiment and take risks (OECD 2021).

“Thus virtual agile organisations derive their competencies from flexible, integrated, customer-driven work processes and structures, which seamlessly integrate partner, supplier and customer sites into a dynamic value network.” (Benton 2019)

Conway’s Law & User Focused Structures

Organisational structures can influence the structure of how services/products are designed and delivered. Conway’s Law (Conway 1967, Skelton 2019) recognises the inadvertent repercussions of organisational structure in the design of the systems they deliver, a particularly frequent issue for public services that end up reflecting the structure of the organisations they are built by (MacCormack, Rusnak and Baldwin, 2008).

Concepts of ‘Virtual Organisational Structures’ (Davidow & Malone 1992, Magretta, 1998) is another key component of contemporary organisational management. It refocuses organisational hierarchy towards the end-to-end citizen (user) value streams across traditional organisational silos. A case study from Australia highlighted by an OECD report (2021):

“This was experienced by the Digital Transformation Office (DTO) in Australia in 2015 when they identified 1027 government websites which were found to be aligned to the siloed structure of government agencies with little connection between the underlying digital services. With a mandate to provide services that meet the needs of citizens, rather than reflecting the structure of government, the DTO established the role of ‘Service Managers’, a senior executive with responsibility for the “whole end to end user experience” of services across and between government organisations. Structuring public sector teams and their leadership to reflect user journeys can be an effective way to counter the effects of Conway’s Law.”

|

Team Topologies and Cognitive Load

An Ideal “team” is one which is small (between five to nine people) and is long-lived. The number of optimal team members was arrived from anthropology research into the number people which human relationships can maintain a degree of trust to form productive relationships required for teamwork. For example, Robin Donbars found that fifteen to be the limited people can deeply trust and five people the limit to hold close personal relationships and working memory (otherwise called Donbars Number). Team sizes are further explored in terms of scaling teams for greater corporation, with groups of teams (or tribes) being no more than 50 people (or 150 people in high trust environments) and groups/divisions being no more than 150 or 500 people.

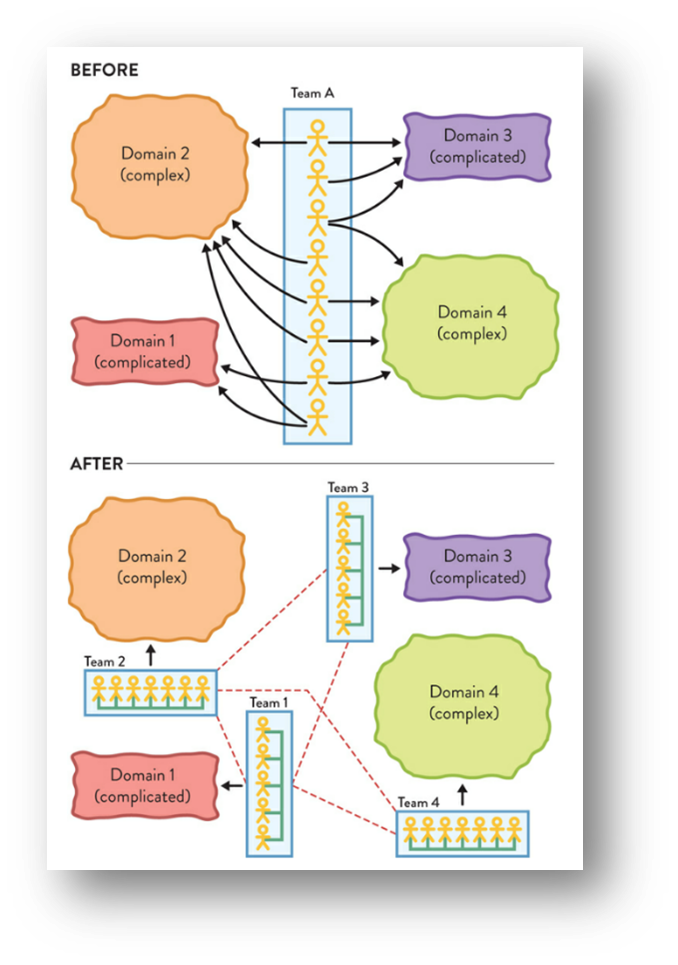

The book Team Topologies (Manuel Pais and Matthew Skelton, 2019) explores different approaches in structuring teams to deliver better flow. While this whole book cannot be covered in this blog post (it’s a good read!) one key element includes exploring the cognitive load of teams. It highlights all too often teams are given greater responsibilities and are caught in a trap of being spread thinly across a range of different responsibilities and continuously context switching, which costs in reduced productivity and even burnout. The book argues that teams need to be put first and advocating for restricting work based on cognitive load.

To address cognitive load, it recommends identifying the different domains of work each team must deal with and classify different streams of work as either ‘simple’, ‘complicated’ or ‘complex’ (needing discovery). Once identified adopt the following guiding heuristics:

To address cognitive load, it recommends identifying the different domains of work each team must deal with and classify different streams of work as either ‘simple’, ‘complicated’ or ‘complex’ (needing discovery). Once identified adopt the following guiding heuristics:

- Assign each domain to a single team. If a domain is too large for a team, instead of splitting responsibilities of a single domain to multiple teams, first split the domain into subdomains and then assign each new subdomain to a single team.

- A single team (considering the golden seven-to-nine team size) should be able to accommodate two to three “simple” domains.

- A team responsible for a complex domain should not have any more domains assigned to them—not even a simple one.

- Avoid a single team responsible for two complicated domains.

Evolutionary Change

The book Reinventing Organisations (Frederic Lalouxm 2014) helped to summarise the evolutionary change in organisations paradigms, which it argues is evolving at an accelerating rate. The book highlights the shift from Red through to Teal organisations, one which has seen a shift from command authority and fear to drive productivity (e.g. Mafia style organisations) to towards empowerment and purpose driven organisations and individuals.

As organisations transition through the different levels of organisational evolutionary change, it brings about different approaches to leadership styles, organisational practices (including decision making) and structures. For Government, this organisational change can be difficult due to the perception that greater empowerment equates to increased risks. The mantra is normally not to try and rock the boat – with the fear of many senior executives being lambasted by an audit office, media or being called up to “please explain” in front of an parliamentary inquiry. This approach to risk unfortunately sees many public sector organisations stuck around the yellow organisational domain.

There is hope however for public sector organisations! Key practices and principles can be adopted overtime to help in this transition, and many are further explained in the Reinventing Organisations (and other resources) including various successful case studies. Some of the key domains of teal practices to explore include self-management (empowerment), focusing on individual wholeness (personal learning and providing a caring supportive environment) and evolutionary shared purpose for both the organisation and individuals.

----

Julian Smith, Director, APSC

Product Manager APSJobs

Member Experience & Specialist Advice Team

Head of Agile Practice